Without Yeasts there would be no fermentation and thus no wine. Here are some important facts about those little helpers you may not know.

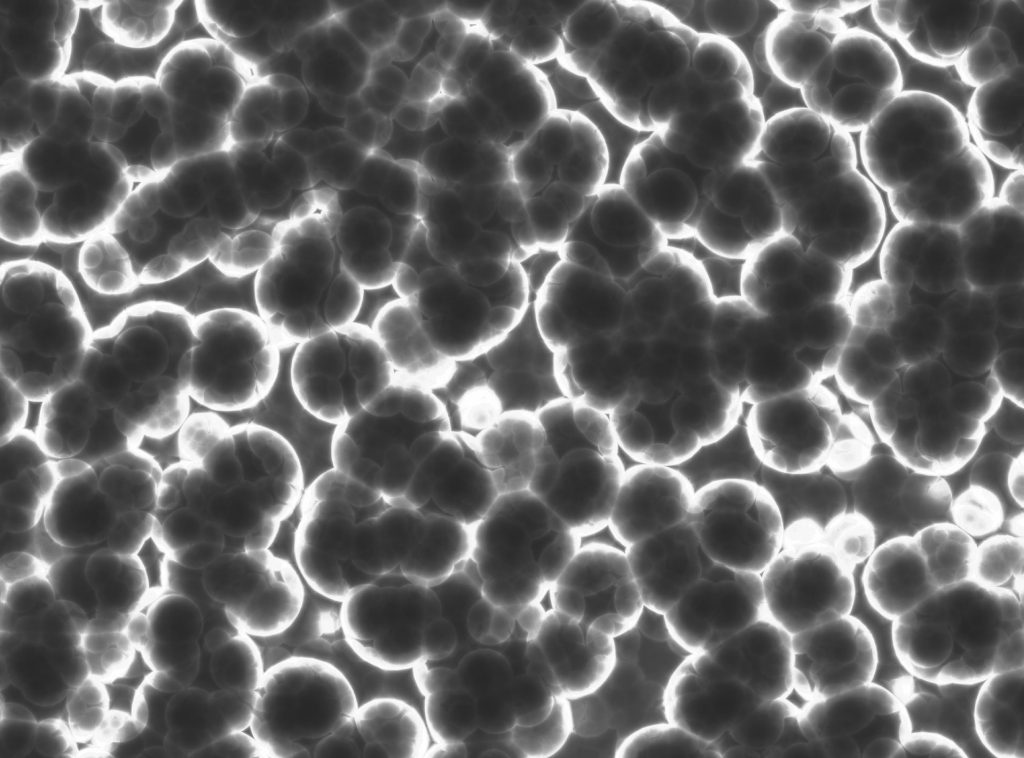

A Tiny Microorganism playing a big part: Yeast

Yeasts play a major role in winemaking. They are responsible for the transformation of the sugar present in the grape must into alcohol (and a couple of other things). It is a topic well covered and we continue to discover more and more about it, but here are six things you might not know about yeast yet.

The Discovery of Yeasts

A lot of people know that Louis Pasteur discovered the cause of fermentation in 1857, but what is unknown that he wasn’t looking so much into the fermentation of grapes for making wine.

At a time when he was the dean of the Faculty of Sciences in Lille, the father of one of Pasteur’s chemistry students approached him since he struggled to produce alcohol from beetroot. Thus, Pasteur set out to prove that a microscopic plant caused the souring of milk, something we now call lactic acid fermentation and which plays an important role elsewhere in the production of wine. Back in the day though, Pasteur’s work was invaluable since it showed that little living cells – the yeast – were responsible for turning sugar into alcohol and that at the same time contaminating microorganisms could turn the fermentations sour, which, of course, could be killed off with heat or pasteurizing it. That’s not always the best approach when making wine, but that’s a different story.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Talking about famous scientists, Emil Christian Hansen followed up on Pasteur’s work and applied it to the making of wine, showing that yeasts are coin with two sides. On one hand indispensable for transforming sugar into alcohol and developing some of the aromas that make wine so special (we get to this in a minute), yeasts are also responsible for wine flaws: the controversial Brettanomyces at lower levels adds to the complexity of wines by adding aromas of barnyard and cat’s pee (which sounds worse than it is in great wines from Burgundy, for example), but Brett as it is called more commonly can easily spoil the wine at higher concentrations. The vinegar tinge, too, can be caused by yeasts producing acetic acid and result in that pricked sensation, which is a pretty unpleasant defect in wines. Yeasts can also result in both oxidation or reductive wine faults as well as a number of other wine flaws and taints.

“Great Burgundy smells of s#@%!”

Anthony Hanson in his book on Burgundy

Beer on Wine

Staying with Hansen, he is, of course, most known for discovering Saccharomyces Carlsbergensis, the yeast used for brewing beer (as the name gives away, it was cultivated on behalf of a Danish brewery that employed Hansen) and possibly the most important species for the fermentation in wine, supposedly in 1883. That’s at least as far as most wine books go, since Max Reess isolated and classified the same yeast Saccharomyces Pastorianus in 1870 (choosing the name in honour of Louis Pasteur). Hansen actually described his discovery under said name not until 1908 together with other work. Great job by both though.

The Cultivation of Wild Yeasts

A crucial argument among winemakers is the use of cultured yeasts versus spontaneous fermentation through wild yeasts that are indigenous to the environment of the cellar. Cultured yeasts give more control over the winemaking process and reduces the risks of an unwanted outcome. On the other hand, indigenous yeasts that can be found in the respective vineyard or winery are the more natural choice and add to the differentiation of wines. Why not take the best of both worlds and cultivated the wild yeasts of a specific winery to add an element of control? That’s exactly what the people at Tenuta San Guido, the makers of the famed Sassicaia, tried a few years ago when they collected the indigenous yeasts after the fermentation in one season, cultured them and tried to use them to get the process started again in the following year. What sounded like a great plan led to the discovery though that the yeast had changed over the course of the year and thus the result, but that’s probably why they are called wild yeasts…

Canaries in a Coal Mine

Fermentation doesn’t just convert sugar into alcohol though but creates a few other things, too, most notably carbon dioxide (CO2). This is a most welcome result in the production of sparkling wines where the secondary fermentation in the bottle produces carbon dioxide from the liqueur de tirage, which generally consists of sugar and additional yeast. However, carbon dioxide is an odorless gas and since it is heavier than the lighter elements in the air like oxygen, it displaces the latter pushing it up and out and thus creates a dangerous environment. Since you don’t smell CO2, it can slowly fill up a cellar without ventilation or vat and suffocate anyone entering it, which has been the cause of many accidents in wineries, sometimes with fatal consequences. Alarm systems for air quality have reduced the risk to the traditional low cellars, but incidents still occur.

The Yeasts that just keep on giving

Once the yeast has transformed all sugar or fermentation reaches certain alcohol (usually about 16% vol.) or temperature, the yeasts die and sink to the bottom. Through filtration, they are removed and the wine moves to the next stage like aging in barrique or bottling. The lasting influence of yeasts doesn’t just stop with the transformation of sugar into ethanol and carbon dioxide though. The yeast is actually responsible for creating some 400 molecules that form the aromas in wine out of a total of 800 we know about. The impact of yeast on the eventual characteristics of the wine even during bottle maturation. An example would be the typical passion fruit aroma you often find in Sauvignon Blanc or lychee in Gewürztraminer. So, yeasts just keep on giving.

The Bottom Line

Yeasts are a popular topic in literature and academic research, but it stills seems that we know only a little about those tiny microbes and how they can influence wine. Despite the discoveries in the last 150 years, much more waits to be revealed. In any case, discussions between traditionalists and modernists on polarising topics like indigenous yeasts look to stay with us for a while. But that doesn’t need to be a bad thing, right?