Shorter ripening periods and hotter harvest – how winegrowers can protect the crop and why artificial snow is not a solution to the problem.

How climate warming changes harvests and why

There aren’t many things about the Covid-19 pandemic that you could think of positive aspects. One of the few upsides has been the increased access to information that previously was not available. The forced digitalisation of the wine sector has in that sense changed things completely. Think only of the number of virtual tastings as an example. While these often provide little value, other virtual events like trade fairs or industry gatherings can be an invaluable source of information. In Germany, every year around this time numerous encounters between wine producers, service centers, solution providers and consultants usually take place across the traditional wine producing regions, but not this year. At least not in the way it used to be. A good example were the 72nd edition of the Rheinhessen Agricultural Days, which this year were combined with the 65th Kreuznacher Wintergathering (you can tell that these events go back a long time) to form the first edition of the digital Agricultural Winter Days of the rural service centre of Rheinhessen-Nahe-Hunsrück that looks after the biggest wine region in Germany.

Harvest and Crop Handling in Hot Climates

One of several presentations by the experts of the service centre discussed the harvesting and handling of the crop during hot periods in German vineyards since even north of the Alps in traditionally cooler climates, global warming has changed the way things need to be done. The ripening period in late summer and early summer is often significantly shorter and harvest has to take place much earlier than it used to be.

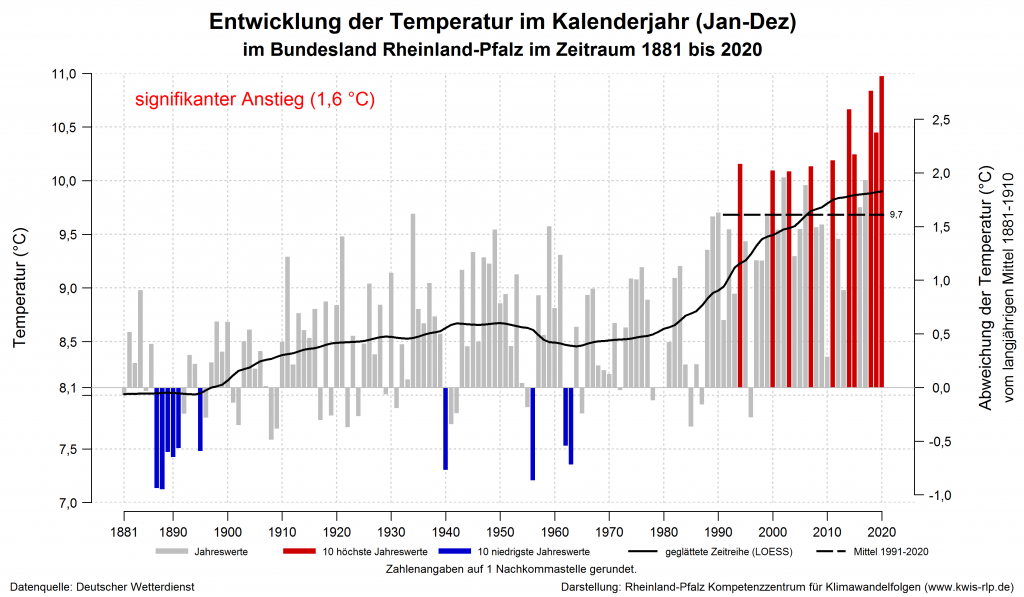

It becomes evident when looking at development of average temperatures compared over the last 140 years, which shows a substantial surge during the nineteen-nineties und an continuous increase over the last couple of years with an annual rise by 1.6 degrees Celsius:

Source: Rheinland-Pfalz Kompetenzzentrum für Klimawandelfolgen

Obviously, that’s not great for the crop and the must that is extracted from it. As a result, you would seldomly see mechanical harvesters in action since they were mostly during the night with harvesting starting as early as 3 am in the morning. The situation is a little bit more tricky where mechanization is impossible, e.g. on the steep slopes of river benches, or where manual harvest is the preferred option. Unless workers are fitted with headlights, crews need to pick the berries during the day when temperatures are far from perfect and can influence the quality of the crop and must negatively. Which takes us to the Albedo effect and its impact.

What is the Albedo Effect?

What is the Albedo effect though? Well, albedo is the measure used to determine the diffuse reflection of a body that in itself is not radiating or in other words how much of the sunlight is reflected by bodies like, the moon or other or other celestial bodies, for example. The value is measured using an albedometer and given in percent or on a scale from 0 to 1. In the same way, the reflection of various surfaces is determined. Snow or clouds can reach a value of up to 0.9, which means that up to 90% of the sunlight is reflected by surfaces covered in snow (which, by the way, is one of the reasons why you get tanned so quickly when skiing in spring), whereas grass only reaches 0.18-0.23 and asphalt just about 0.15 albedo.

The reflection of sunlight from snow-covered surfaces is several times higher than from grass.

If there is only a small amount of sunlight being reflected, though, it means that a large part of the energy coming from solar radiation is absorbed by the surface and in consequence the body itself. Because dark surfaces absorb more energy than light ones, the effect with dark berries is stronger than with green or light skin. However, the upper cell layers and stems pick up more heat as a general rule and things only get worse by picking and dropping into bins, especially in the centre of such containers.

Why is that the case? A good question and even with a limited knowledge of thermal physics such as in my case, we all understand that the skins of the berries conduct heat not as well as must since solids have a lower conductivity than limits. Or in an example, the heat of sunlight is distributed more evenly in a lake than in a closed compartment filled with water like a berry that stores the heat nicely in its pulp.

Average temperatures of 21-23 degrees that are a fair bit above what we were used to therefore translate to an additional 1 to 3 degrees in the must.

Practical Consequences for the Harvest

So, what should wine producers to address the problem? Well, the use of artificial snow as a to bounce back some of the sun’s rays might a bit extreme and fairly practical. The service centre, however, focuses on two options:

The first option would involve the crushing of the grapes in the evening after the harvest over the course of the day and moving them into a cooling cell. That causes excessively high temperatures and increased phenol extraction though if the must is left for too long in contact with pulp and skins.

Crush them or keep them in the crate?

Alternatively, you could consider putting the grapes as a whole in cold storage overnight in light of the increased temperatures. The basis for this consideration takes us back to what we discussed above, i.e. the berry could be considered the smallest and best juice container, simply because no biochemical processes are triggered while the berries are kept intact. Still, because even the experts seem to have very little data or information about the actual effects on the final product when using such an approach, the recommendation is still a combination of both options:

That means crushing the grapes that have been harvested during the morning immediately thereafter. Grapes picked in the afternoon should be crushed in the evening and subsequently cooling down both batches of must overnight.

Considering that we are only at the beginning of harvesting in warmer climates, this does not appear the conclusive view but the best possible solution for the time being until further information or other options are available, so we will be talking about it some more – and in the meantime, the headlamps for the night harvest are perhaps the easiest solution.